Fleming Changes the Recipe for a Bond Thriller in From Russia With Love

When Ian Fleming confessed to writing “fairy tales for adults,” he was not only being entirely serious, but playfully literal. His James Bond thrillers weren’t all based on actual fairy tales, of course, but some of the best of them owe a debt to the Brothers Grimm, French storyteller Charles Perrault, and Walt Disney. Perhaps Disney should get the lion’s share of credit.

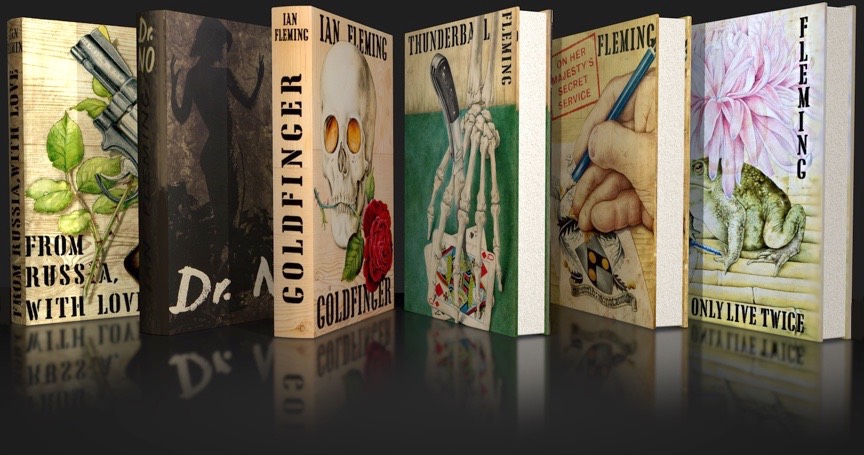

The first six Bond films, released between 1962 and 1969, cemented the public's expectations for a standard Bond adventure: high living in exotic locales, romantic dalliances without commitment or consequences, colorful villains, outlandish schemes, and assorted action set-pieces of varying degrees of incredibility. The six were all adapted from books which Fleming wrote during the final two-thirds of his career, after he had found his footing and his muse.

His muse appears to have been Walt Disney.

The plot of the very first Bond novel selected for filming, Dr. No, seems to chart a parallel course with a live-action Disney adventure film from 1954. The second Bond film, based on Fleming's previous book, From Russia, With Love, borrows many of its story elements from an animated Disney classic released in 1950, combined with characters from another Disney film which was still in production as Fleming finished typing his manuscript.

Fleming seemed to get wind of where the Disney train might be headed next, and managed to get to the station ahead of it. When Disney turned his attention to a fantasy about a wee red-haired man who granted golden wishes, so did Fleming. Darby O’Gill and the Little People was released three months after the publication of Goldfinger.

Prodded by the Broadway success of Lerner and Loewe’s Camelot, the Disney team dusted off a long-dormant project based on the first volume of T. H. White’s Arthurian tetralogy, The Once and Future King. Fleming countered by shaping the Medieval Arthurian romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight into that James Bond thriller with the cumbersome title. The Sword In the Stone and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service reached the finish line together in 1963.

So, why should we imagine that any of Ian Fleming's novels are based, not just on fairy tales, but the Disney version of those tales? We only need to glance back at the book where, inspired by his mentor Raymond Chandler’s remark that each of his recent thrillers had been worse than the last, Fleming decided to give it all he had.

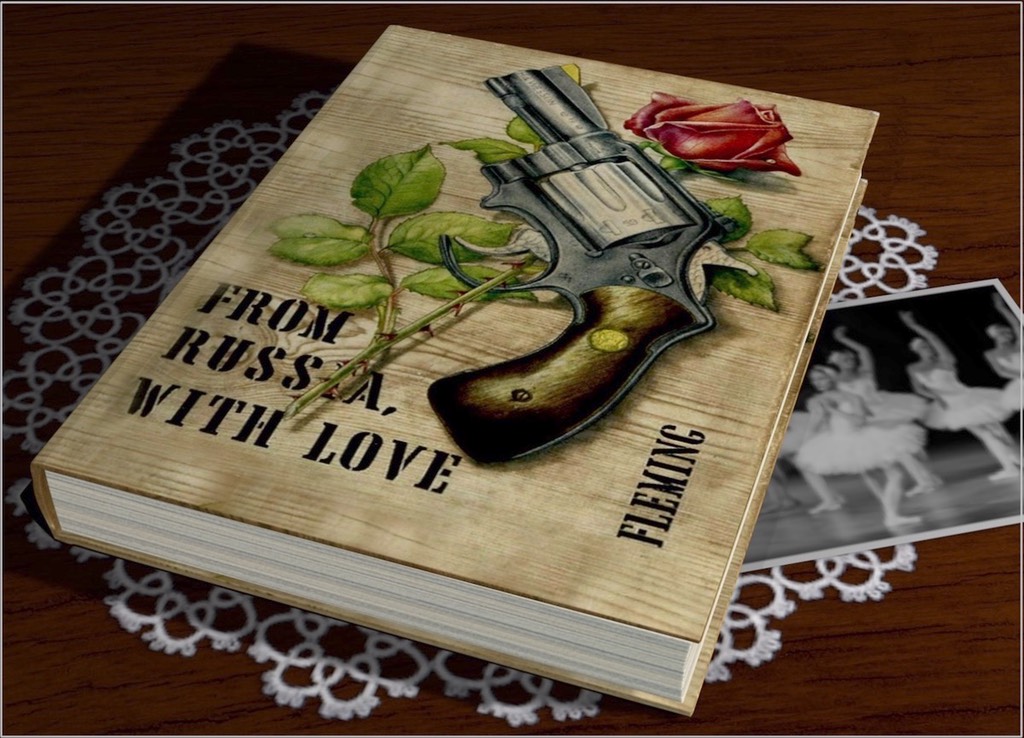

Within the first few pages of Fleming’s fifth novel, From Russia, With Love, a dragon is summoned by an evil old crone who, as we will later learn, owns a set of poisoned needles.

At the climax of the story the beast stands guard over a slumbering princess to prevent the handsome young hero from disturbing her eternal nap. Fortunately, her rescuer has been equipped with a sword that can pop into his hand as if by magic.

LINKS TO RECENT POSTS

“HAVE GOLDEN GUN, WILL TRAVEL"

Was Fleming a fan of Paladin?

Tying the knot between FRWL and Disney’s Cinderella

Disney cartoon critters in FRWL

A bilingual anagram in Goldfinger

Fleming tips his hand in Dr. No

"THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE BROCCOLI”

Oscar night for 007

In addition to being a solidly-grounded spy thriller, From Russia With Love has been supplied with most of the characters and essential props from “Sleeping Beauty,” which was at that very moment being turned into an animation masterpiece by the Walt Disney Company.

But there’s more than one connection here with a Disney film - in fact, more than one animated Disney film based on a fairy tale. Until the moment when a beautiful former-ballerina reprises a role which she may have danced years earlier on a stage in Leningrad, she is forced to be part of a perverse Cinderella-story.

Instead of scheming to prevent her beautiful stepdaughter from arriving at the Palace and being introduced to a prince, Rosa Klebb arranges for Tatiana Romanova to stay at the Kristal Palas - James Bond’s hotel. As Bond takes his bedtime shower, she will enter his room and slip between the sheets clad in nothing more than Cinderella’s black velvet choker. “Fairy tales for adults” apparently meant the Disney version, plus steamy sex.

Several other refugees from the 1950 Disney Cinderella are given meaty roles. Those thieving mice which the compassionate young animated heroine befriends, her family’s faithful hound Bruno, and a malevolent feline named Lucifer are transformed, as if by the wave of a fairy godmother’s magic wand, into a band of gypsies, the hero’s stalwart confederate, Darko, and the cruel Krilencu, who, like Lucifer, will be chased out of a high window to drop to the cobbled street below.

Beauties, Bloodhounds and Skulking Villains from Walt Disney’s Cinderella and MGM/UA’s From Russia With Love

This is how Ian Fleming began to reinvigorate his spy series with From Russia, With Love, setting off a run of entertaining novels based on fairy tales, Disney films, and Athurian legends. After capturing world-wide attention, the books would be turned into a celebrated series of movies that soldiers on to this day.

What follows on these pages is not meant to be a pedantic dissection of Fleming’s later novels, but a personal story of the sort of small discoveries which have undoubtedly been made by countless casual readers through the years.

I read Fleming before ever getting the chance to see a Bond film, and started reading his books while he still had a few more left in him. When I finally caught up with the films, I watched them out of order, the same way I had read the books - at least the ones that made me keep turning the pages all the way to the end. It didn’t occur to me at the time that the order might be crucial for understanding the long, tangled path of an unlikely hero’s journey.

From Russia, With Love opens with apocalyptic imagery based on a William Blake painting

Although Fleming's thrillers contain some of the standard devices we're told about in school when we study great literature, Fleming wasn’t in the business of writing great literature. He crafted books to be read for fun, books that would sell because they’re a blast to read. When he sprinkles them with recognizable references to classic tales and the popular entertainment of his own day, we’re probably meant to enjoy them as an overgrown schoolboy's spoof of highfalutin writing.

Think of the scene from the film Animal House where a professor (played by Donald Sutherland) who, while discussing Milton’s Paradise Lost, writes “Satan” on the chalkboard and then stands next to the word, grinning slyly as he munches on an apple. The obvious labeling is already amusing, but becomes richer as we realize that it's absolutely true. He really is Satan. As every college student learns, it's part of a professor's job description to open innocent minds and sow doubt.

In a similar vein, when Bond first lays eyes on Honey in Dr. No and imagines her as a goddess, readers should take note. The scene leads to a great payoff when Honey turns out to be an actual goddess - just not the one Bond is thinking of.

In Fleming’s Bond novels we can appreciate the underlying myths, fairy tales and Disney screenplays if we choose to, or just sit back and enjoy the scenery. But even if we smile at the author’s ingenuity when we spot his recurring themes, we understand that they’re not intended to pack the weighty wallop of those Biblical allusions in The Grapes of Wrath or The Old Man and the Sea. When Bond quotes the Bible or even quotes Jesus, it’s not because we’re supposed to view James Bond as some sort of Christ-figure.

Although, come to think of it, Bond is condemned by his enemies and brutally tortured. And of course he's killed and then raised from the dead, so you could probably make a case for it. But not seriously.

On the other hand, by the time we get to Thunderball where the final trajectory of Fleming's Bond saga begins to take shape, if we remember nothing we learned in school about mythology, Greek tragedy, Arthurian Romance, or Middle-English poetry, we're in danger of missing the best jokes.

(A Link to the Bond Blog)

Dr. No Goldfinger Thunderball The Spy Who Loved Me OHMSS You Only Live Twice